thought processes

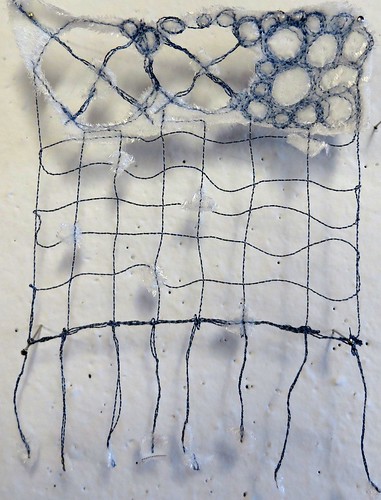

I collect strategies for creating without over-thinking process or materials. It is pretty clear to people who make things for a living (Brian Eno, Twyla Tharp) that the physicality of the product has to be mirrored by the physicality of the process, and too much thinking tends to stilt both.

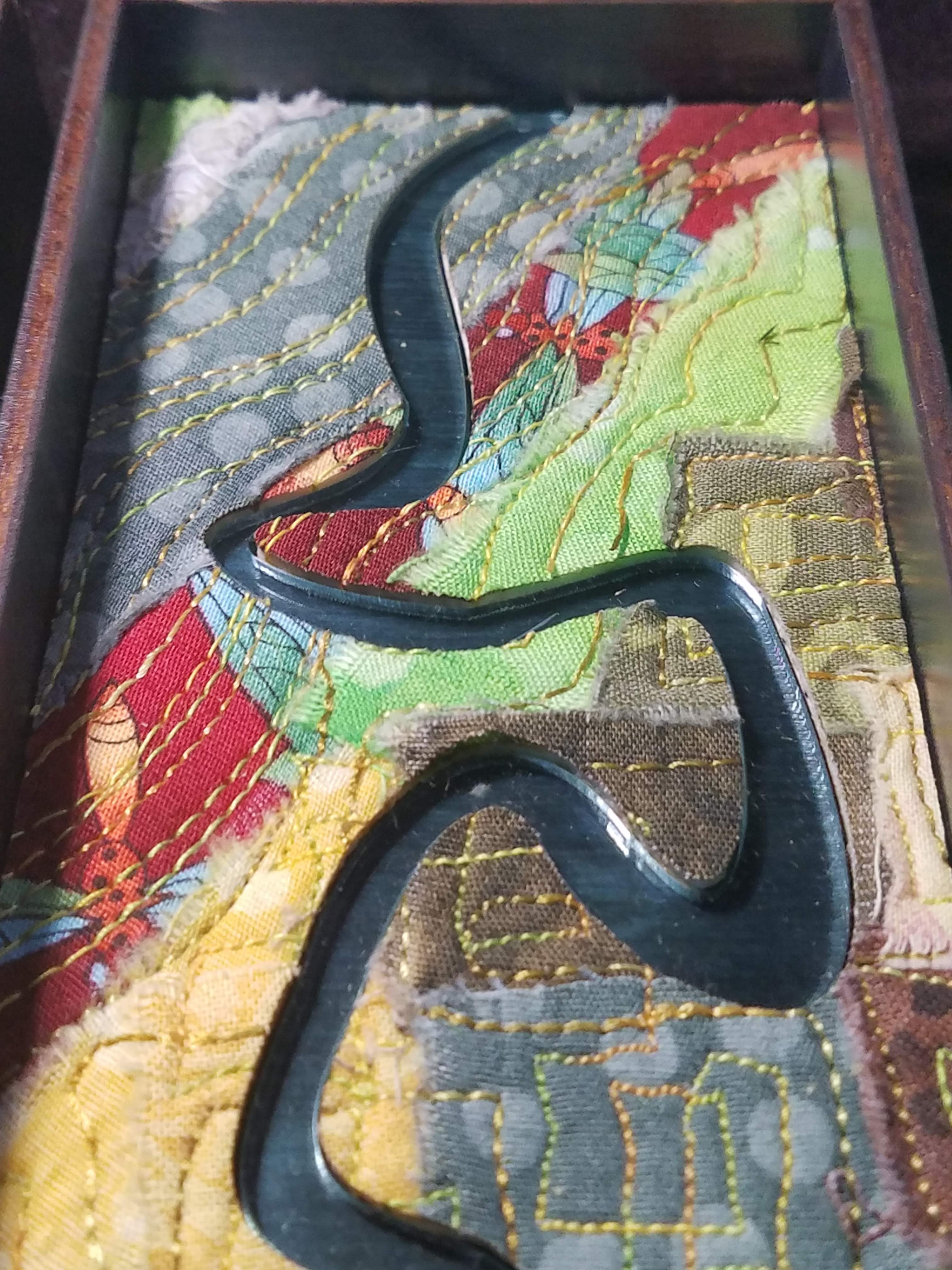

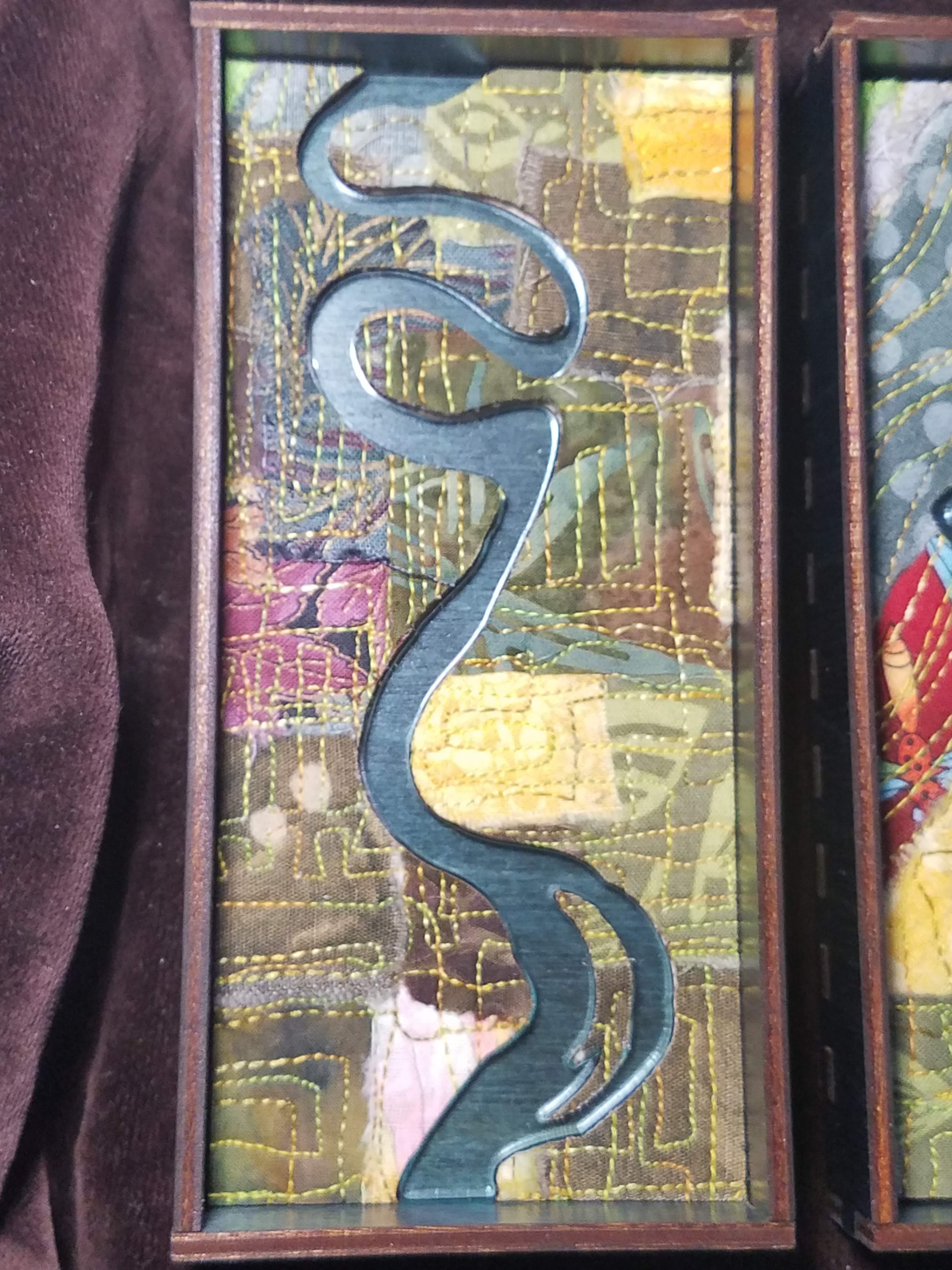

To that end, I have collected a pile of prompts and precepts that I use to poke myself out of a creative rut. The most recent is Brian Eno’s Oblique Strategies, which you can find online daily over here. Today’s missive said “What were you really thinking about just now? Incorporate.”

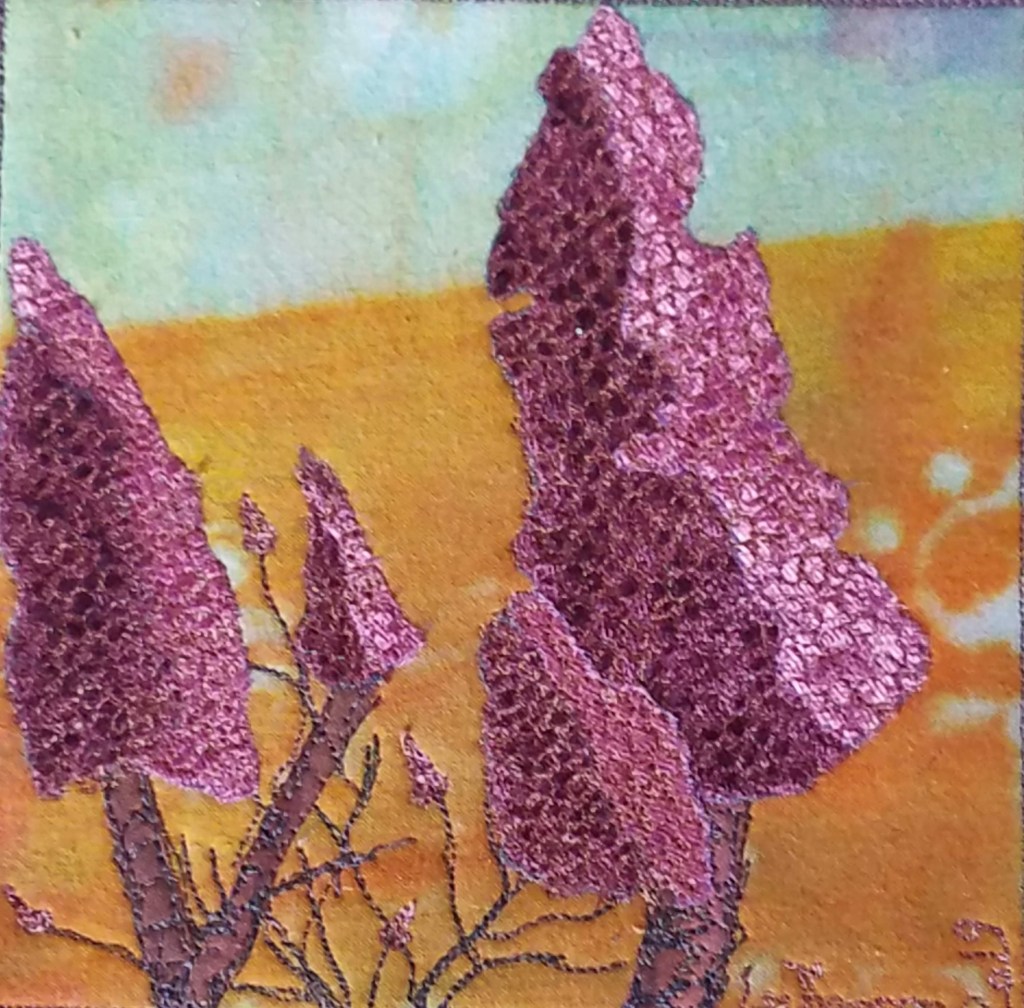

What I was really thinking about was time, and how to demonstrate in a small piece of work the passage of time. But I was also thinking about my father, who is lost in dementia and unsure about a lot of things. He asks me how old he is, and when I tell him (ninety-five) he looks at me aghast. “How did that happen??” he asks. The only answer that satisfies us both is Alice’s answer when I ask her the same kind of thing (“how did you get to be this old already?”). She rolls her eyes, and says in one breath “the relentless, unidirectional passage of time, Mom.” So that’s what I tell my father, and we are both amused until he needs to know that again. Or know something different.

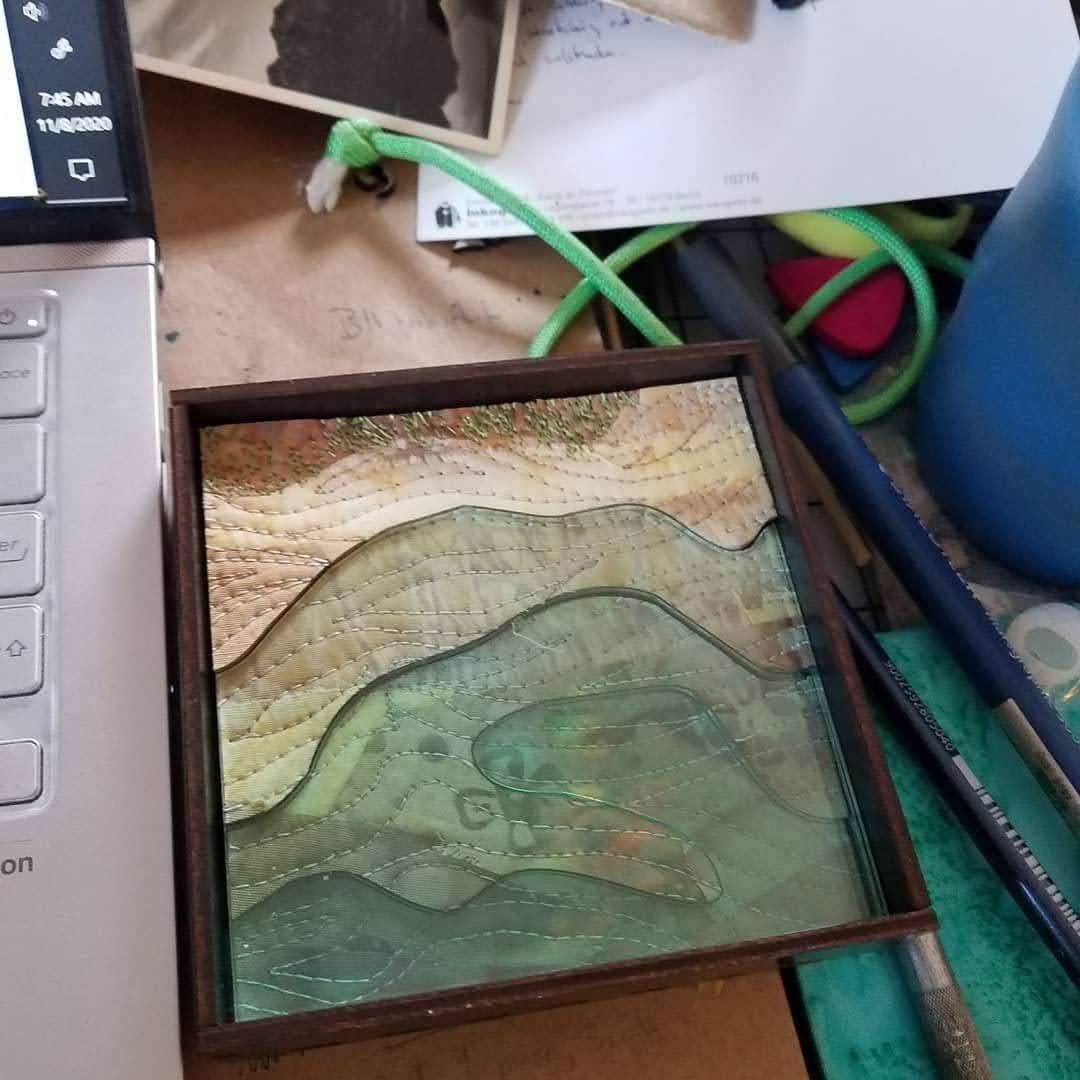

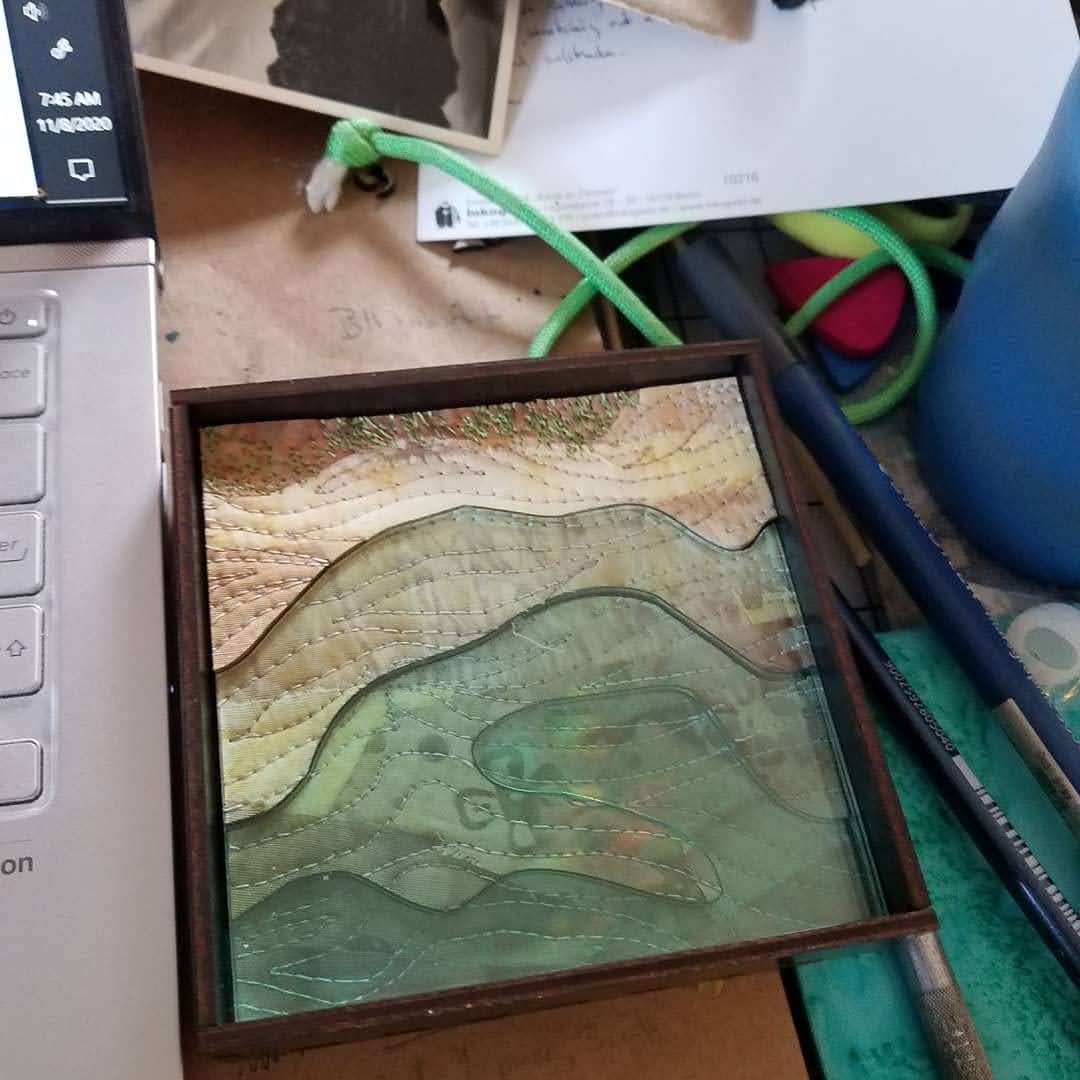

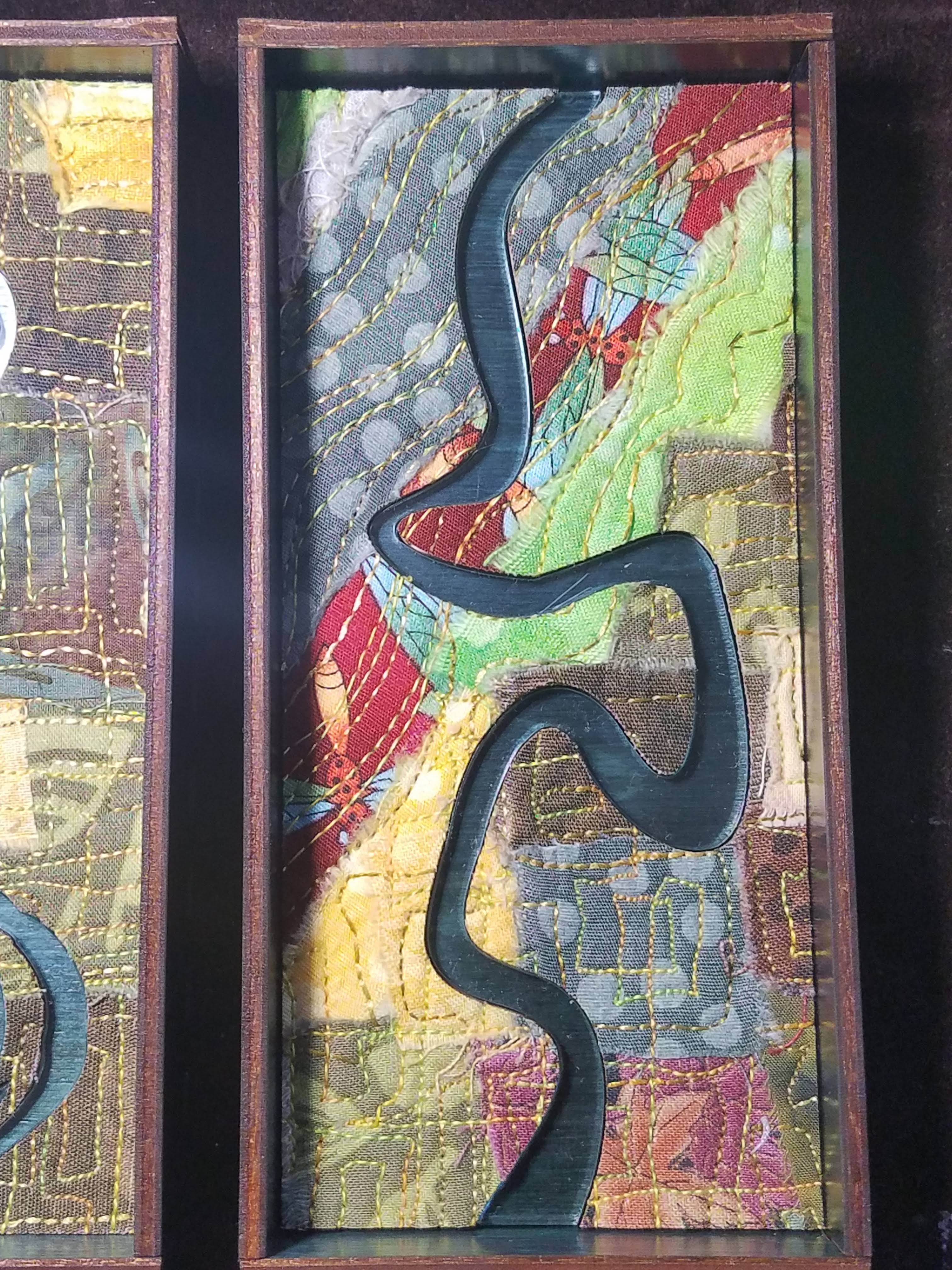

So that’s what I was really thinking of. The relentless, unidirectional passage of time.