Moffen Island

Friends, I have to admit that a couple days into the trip time started to go entirely wonky on me. I can almost trace out our journey on the tourist map of Spitzbergen/Svalbard (the entire archpelago – the town(s) are Longyearbyen and assorted others) but the days are only loosely connected to the trip. So I am pulling sections from my journal of things that stuck out to me.

We stopped in another fjord further north, ringed around with tall peaks. I got up around 3am because I could see stars out of our porthole. Once on deck (swathed in my down coat) I could find the Big Dipper, and from there Polaris. It was wild to have to tilt my head so far back to see it – the difference between 80° off the horizon and zenith (directly overhead) is hard to see! I finally found Orion by waiting til his belt showed over the mountains (I never did see his feet) and from there located Procyon, and Aldebaran. While I was staring at stars, I was wondering what town was producing light pollution on the horizon, until I realized it was aurora. It was faint and flickery, but present and lovely in the cold night.

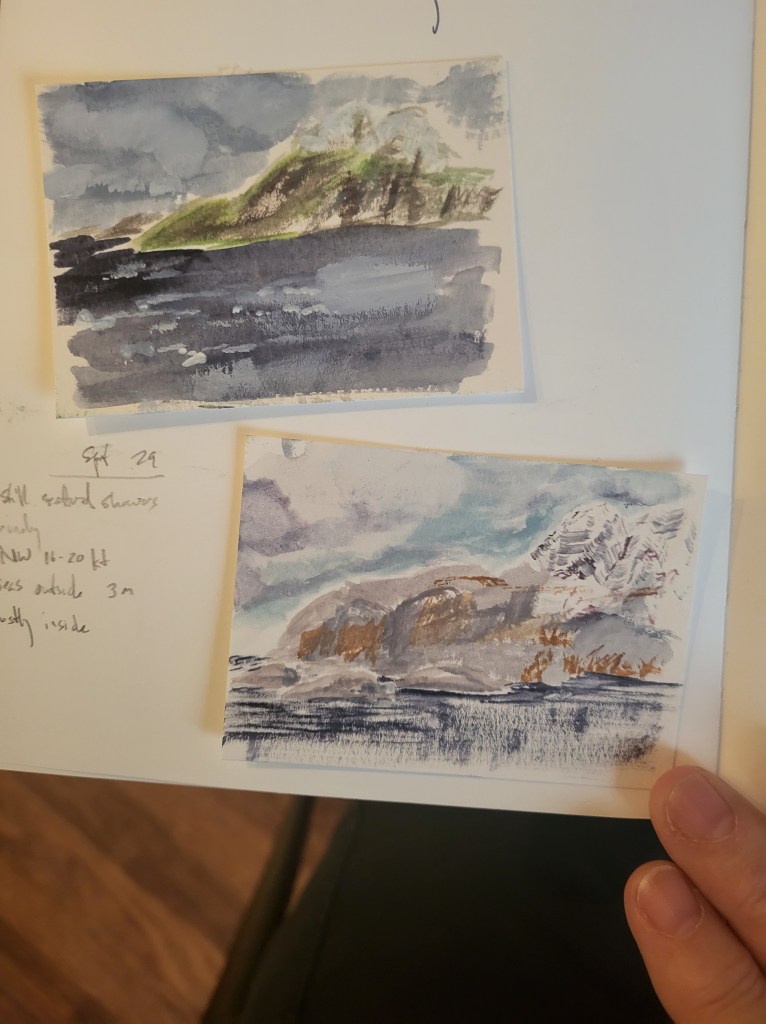

The next morning we dropped off the intrepid hikers among us (about half) and they hiked across the peninsula to meet the ship on the other side. The rest of us did projects ashore (everyone else) or drove around in the zodiac looking for arctic foxes and interesting ice formations (me), which was fun. The 3rd mate and I saw fox tracks, but no fox, while the people at the landing saw two, one in winter colors and one in summer colors. Mid afternoon we upped anchor and went around the point and anchored at a hut on the shore. We could see the hikers coming over the pass between the hills, tiny dots against the landscape. It took hours from seeing them to them actually arriving, and picking them up.

Once we had everyone aboard again we went north. Really, thoroughly NORTH. We went up over the top of the main island of Spitzbergen, and further north than that is a strange island that feels in the middle of the ocean. It is actually part of a large delta, from several large glaciers melting back a lot (not in human history, before that). It is a funny low, round island with a pond in the middle, so it is shaped like a low flat donut, composed entirely of rounded stones between head sized and sandgrains. It is where walruses breed, so it is closed to everyone during breeding season, but we were slightly less than a week past breeding season, so we went closer, to find a place to anchor. In circumnavigating Moffen Island we found a large group of walruses (herd, pod or haul are the usual collective nouns) hauled out on the beach, jostling each other like teenagers. We anchored slightly north, and everyone wanted to land. Once ashore, half of us went right, to see the walruses up close, because too many would be distracting, and the other half went left, to draw, take pictures or make performance art. We were as far north as we would get, there was nothing between us and the North Pole except 10° latitude of ocean and ice. It was beautiful, and desolate. While we were walking I kept lagging behind to look at all the small perfect stones, and one (possibly two – individuals were hard to ID) walrus(es) swam along the beach watching us. At one point one hauled himself partway up the beach, to peer over the berm. It was astonishing. The people who got closest to the haul of walruses at the other end of the beach said they were jostling each other constantly, and smelled of fish and farts.

While we were there the sun came out from behind clouds in the south and shone across Moffen and towards the snowsqualls in the north, making a high faint rainbow in the snow. We weren’t sure what to call it – snow-bow, rainbow – but it was magical. I had the foolish thought that if I backed up far enough I could get it all into the camera view, but eventually decided it wouldn’t work quite that way.

We left Moffen with some regret, but there was weather coming. We went south (everywhere is south from there) and east, to Nordaustlandet (Northeast Island) and found Lady Franklinfjorden. When Franklin was lost, his wife poured money into high latitude exploration hoping to find something about where he’d gone, and people exploring in her name would name things after her. There was a glacier there with edges we could hike up to, and more ice in the ocean. We went ashore and climbed about in the moraine area, and some went closer to get a better look. Because it was going to blow hard from the east, the captain took us around the corner to Murchinsonfjorden, and brought us deep into the center of the island. It took two anchors to hold us, even with tall peaks all around. The 2nd mate confidently assessed the wind at Beaufort 8, which is 35-40 knots and a Full Gale. The wind whistled in the rigging, and there were whitecaps in the small harbor we were in. The sound people had a field day recording the wind humming and moaning around the ship. When the wind dropped later in the afternoon the intrepid ones went ashore to hike up high enough to see the ice cap in the middle of the island. They turned back early because their guide saw a bear, though no one else did. Later she swore with a straight face that she was just tired of walking, but we are all pretty sure she did in fact see a bear. That was the only time we had to retreat for a bear, but we had the guides there with us all the time to keep us out of exactly that sort of trouble.